Being a Man, Being Me

A Meditation on International Men’s Day

To mark International Men’s Day (November 19), I wanted to pause and reflect on what being a man has meant for me — not in the abstract, but in the long shadow of family history, social change, and the world we inhabit now.

This isn’t a polemic or a manifesto. It’s simply one man’s attempt to understand the forces that shaped him. If any of these reflections resonate, I’d welcome your thoughts — and you’re very welcome to share the piece.

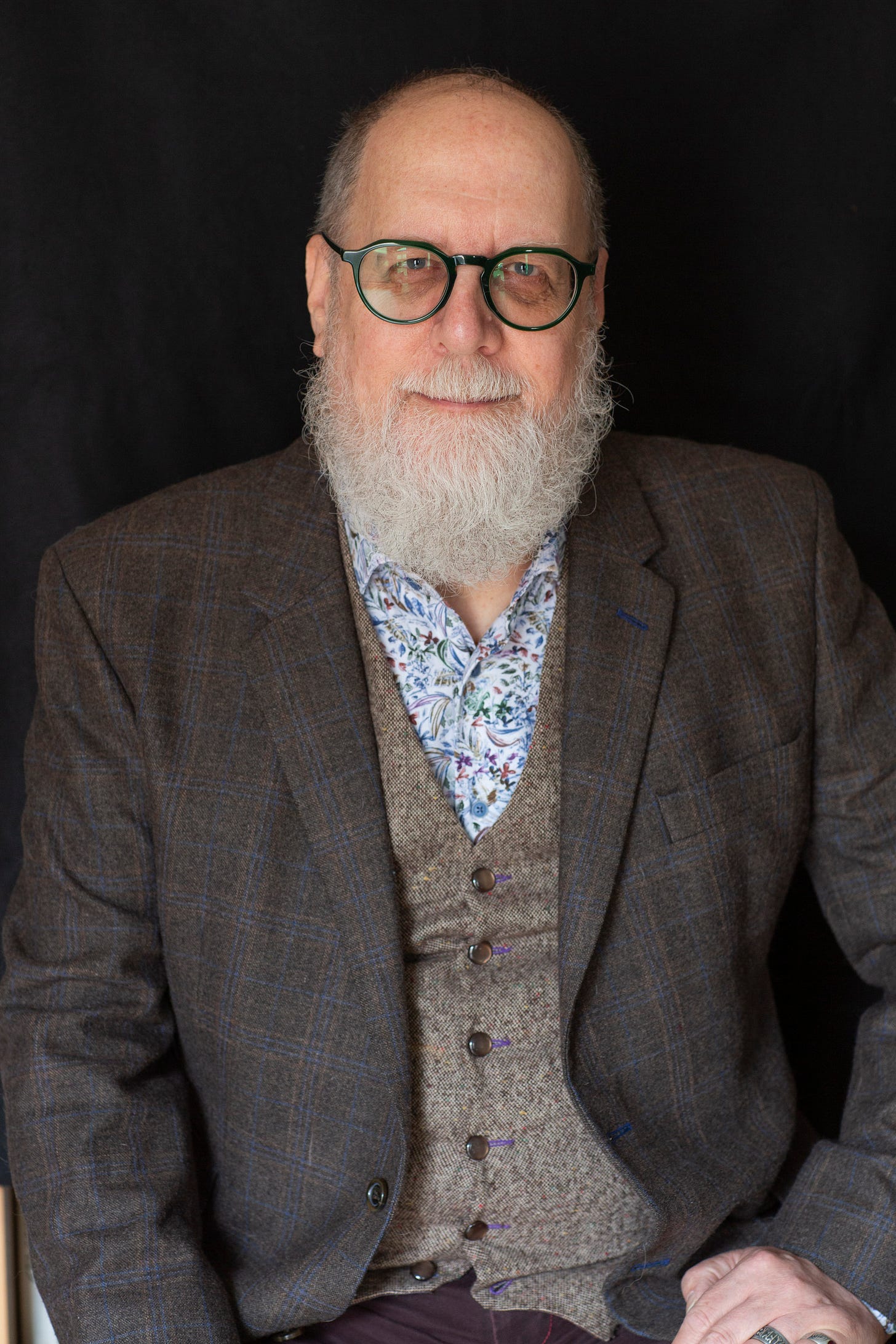

Real life; a portrait of the artist as a man

Introduction

This essay isn’t an academic treatise, or a solution to the world’s ills. Neither is this a prescription for anyone else. I am merely considering the forces that have shaped the man I have come to be. It is a very personal series of thoughts on being a man and thinking about International Men’s Day (November 19). I don’t have any secret sauce, and I don’t have any great mysteries to share. But I do hope that what I say here will offer some useful insights – that you are free to ponder or reject as you will.

Categories

I must admit that from the start, I am uncomfortable with trying to write about myself within this category of “man”. That label is only one of many that I could use to describe myself – each with its own perspective and lived experience. I am white and UK born. I am straight and cis-gendered. I am well educated (grammar school followed by university). I am retired, and I live on a modest pension – and I’ve worked most of my life (with a spell as a house husband). I’ve been married twice and divorced twice, and I have three children.

These are all standard labels, but what about the stories they don’t tell – the real me and not the assumptions you could make about me? Yes, I am white and UK born, but my dad was born in India where my grandfather was a Lt-Colonel in the Imperial Indian Army. My dad was public school educated and subsequently served in India and Burma during the 2nd World War. My mum was born in New York, to a dad who was a first-generation Scottish immigrant, and a mum who was a second-generation U.S. immigrant born to a first-generation German/Jewish immigrant dad and a first-generation Danish mum. My mum ended up living in the UK by accident – her parent’s ship was sunk by a magnetic mine as they were leaving the UK to return to the U.S. during the early years of the war, and her parents chose to stay in the UK as a safer option.

I was bullied, a lot, at school. I was extremely skinny, wore glasses, and I didn’t fit into any group – so I was the perfect target. I’ve been made redundant 5 times and been admitted to hospital after a nervous breakdown. I was recently diagnosed with Autism and ADHD (which explains a lot), and the longest I’ve lived in one place since leaving home is 13 years, and I am now having to find somewhere new.

And what about all the other categories I could use about myself? I’m a musician, I’m a writer, I’m comparatively healthy, I’m a human being.

Yet, the category that generates the most heat, and I suspect the least light, is the binary of man and woman, and what it means to be either category in today’s society. But before we discuss what it means to be a man or a woman, we need to look at the impact of history, and today’s societal pressures.

Historical Context

Most of us come from societies that are still, or were until recently, strongly patriarchal – with strictly imposed gender norms governing rights and “appropriate” behaviour. These societal structures, while widespread, are not universal. The Minangkabau in Indonesia, the Mosuo in China, and the Khasi in India display strong matrilineal and matrifocal characteristics, where women hold significant power, property passes through the female line, and female elders are central to the social structure.

For the rest of us, even in the “liberal” West, women have had to fight for the rights that we men take for granted. In the UK alone, women were only granted equal voting rights in 1928, while the Equal Pay Act and the Sex Discrimination Act were only passed in 1970 and 1975 respectively. Compare that to the long history in UK society where women were seen as physically, mentally, emotionally and morally inferior to men.

Those roots run deep, embedded in family histories and unspoken assumptions. My own dad firmly believed men were more intelligent than women, and that this was demonstrated by the lack of well-known women artists and scientists. (What I didn’t know then was the long and shameful history of men excluding women from those pursuits, men appropriating women’s achievements as their own when they were able to make a mark – or just writing them out of the narrative so they were lost to future generations.)

And there are now strident voices who want to take us back to those earlier times – who use a false and rose-tinted narrative of the past to critique the present. They want to persuade us that “traditional values were what made us great”, rather than admitting that those very traditional values imposed appalling burdens on individuals and communities who lacked power.

Current Pressures

This rebalancing of human rights, alongside the economic and societal impacts of two world wars and ever-accelerating technological change, have significantly altered societal landscapes – and up-ended all sorts of long cherished norms.

Here in the UK, the aftermath of the 2nd World War drove the creation of a general welfare society – including the NHS with its revolutionary “free health care at point of access”, and the widespread provision of social housing. I also benefited from a university education supplied free-of-charge, and a full grant for living expenses (until my final year). Those improvements have largely stagnated, or been gradually rolled back, since the Thatcher years, worsened by the collective insanity of Brexit where we cut ourselves off from the biggest free-trade bloc on the planet.

In the UK, we have seen a sustained policy of privatising profit and socialising debt – while wealth inequality has grown at an alarming rate. Youth unemployment is rising, and the traditional “social contract” appears to be null and void. Economic uncertainty (including the fear that AI will steal my job), mounting burdens of debt, and a cost of living that excludes millions of young people from the housing market, are undermining social cohesion, and leaving many of us wondering where we fit in – what our role is, and how I can be valued.

So it is that many men are being told to blame woman, or immigrants, for their lack of opportunities – rather than acknowledging that the system is being biased more-and-more to those with wealth and power who want a captive and desperate labour force.

And yes, many men are also being called to account, to address cultural norms that valued women purely for their sexual availability, or encouraged men to bottle up most of their emotions apart from anger. We can’t rely anymore on our ability to earn money, and societal pressure that kept married women in the home, to keep women chained in unhealthy relationships. We men have also lost many of the old roots that gave us a place we believed was exclusive – such as male dominated workplaces, male only clubs (whether strip clubs or football terraces), and seeing men like us in all the positions of power.

And I write this not only as a man in later life, but as someone who acknowledges that many younger men are trying to understand the pressures they face — pressures I never had to face in the same way.

So, What About Me?

I love being a man, but that’s largely because being a man has rarely prevented me from doing what I wanted to do.

I have never faced prejudice or upset societal norms for being a white, straight, cis-gendered, well educated, able-bodied, male. I’ve never been told to “go-home” or been attacked for my skin colour. I have never been judged for holding hands with my partner in the street, or told I’m “stealing a man’s job”, or I’m only in a management role because I “slept my way to the top”. I don’t have to pay a pink tax, such as the injustice of being taxed on period products – or been told I can’t choose to have a vasectomy without my partner’s (and doctor’s) approval.

No one has ever told me to “smile”, but I have been complimented for being kind. And most women I know have suffered at the hands of men, whether sexual harassment, work-place bullying, or domestic violence.

And I have also benefited from the poor behaviour of other men. The bar is set so low that being kind and polite is noteworthy. Some women will be cautious and placatory around me because they have experienced violence at the hands of another man who was rejected.

However, I have also learned from childhood bullying at home and at school – experiencing what it feels like to be powerless, excluded, and unseen. I have had to do a lot of personal work because of my breakdown and suicidal thoughts, and I have been exposed to many alternative cultural viewpoints through my work researching and writing about social justice,

And so it is that I have tried to clarify what it is to be a man – not so much because I don’t know what it means for me, but because it means so much for so many of us.

Simply put, I am a man because I have the privilege of being allowed to be me without any pressure to be otherwise.

But – if I also had to say what that being a man means in practice, I would say it’s about self-responsibility and caring for others.

Self-responsibility means I am responsible for my choices – though I also recognise that I’m not always responsible for the choices that are available to me. Self-responsibility means accepting that I must accept the consequences of my actions, and my inactions. Self-responsibility means acknowledging that I am still learning, and that everyone has something to teach me.

Caring for others includes using my privilege to support those who have less power – to defend those who are marginalised. As a man, my voice carries a lot of power, so I choose to use it to amplify rather than overshadow the voices of women who would otherwise be ignored or discounted.

As a straight cis-man, my sexuality is mainstream and implicitly accepted almost everywhere. But I also believe that gay, bisexual, trans, and other individuals shouldn’t have to justify their existence, or be the target of ignorant prejudice – so I will speak up for them when no-one else will and be safe place where they can be themselves.

It means standing between a bully and his victim, because I know that I project authority and physical strength – the kind that makes a bully think again.

And above all, I want each person to be allowed to work out their own version of what it means to be human, to be accepted for the character of their heart and the authenticity of their actions – not according to some arbitrary rule imposed through prejudice or a knee-jerk appeal to the past.

My compassion (such as it is), has grown as I have learned to love myself, and understand that my value isn’t what I achieve, but the way I make others feel around me. But I must also admit that being a man, just presenting as one, also carries a lot of privilege, and that being a man means understanding how that arises, and the responsibilities that come with it.

And if being a man has taught me anything, it’s that we do not need to perform hardness to be strong, nor deny vulnerability to be whole.